Does your mozzarella refuse to stretch or just burn? The secret is science. From "pasta filata" to the crucial role...

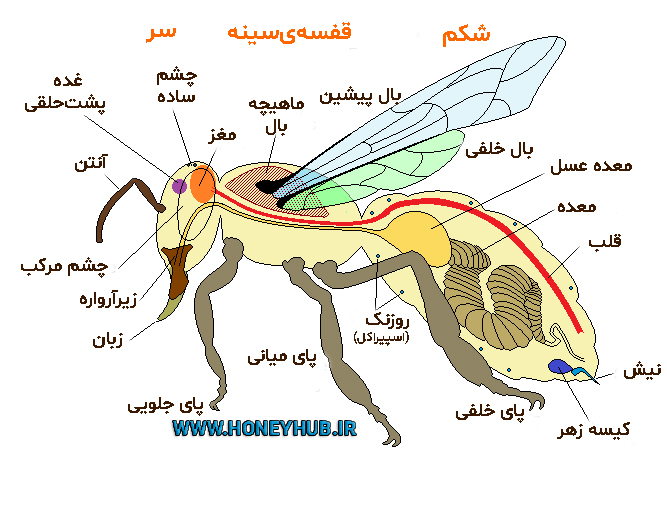

Honey Bee Pheromones: The Advanced Chemical Communication System in Bee Colonies

Introduction

Along with the famous bee dance, honey bee pheromones represent one of the most sophisticated communication systems among social insects. Pheromones are chemical substances secreted by exocrine glands that elicit behavioral or physiological responses from another animal of the same species. In honey bees, pheromonal messages typically target colony members, though exceptions exist where the target may be a member of another colony (Free 1987).

In this post and two companion articles (Effects of Queen Pheromones on Worker Bee Brains and Worker Bee Pheromones), we provide detailed information about honey bee pheromones. We hope this unique Persian-language text illuminates the hidden aspects of queen pheromones for you.

The complex organization of honey bee society, consisting of three adult castes (queen, worker, and drone) and brood, facilitates numerous coordinated activities and developmental processes, thus requiring precise and sophisticated communication pathways. Pheromones serve as the key factor in establishing and maintaining this complexity among colony members, ensuring broad functional flexibility that allows colonies to cope with unpredictable events or changing environmental conditions.

Pheromones are involved in virtually every aspect of honey bee colony life: growth and reproduction (including queen mating and swarming), foraging, defense, orientation, and overall colony activities from establishment to decline.

Pheromones facilitate communication among all honey bee castes: queen-workers, workers-workers, queen-drones, and between adult bees and brood (Thurin and Richard, 2011).

Types of Pheromones in Honey Bees

In honey bees, as in other animals, two types of pheromones exist: primer pheromones and releaser pheromones.

Primer Pheromones

Operate at the physiological level, eliciting complex, long-term responses in recipients and inducing developmental and behavioral changes.

Releaser Pheromones

Have weaker effects, eliciting simple, transient responses that only influence recipients at the behavioral level.

Many known pheromones in insects are of the releaser type. They are classified into several categories based on their functions (e.g., sexual, aggregation, dispersion, alarm, recruitment, trail-following, territorial, identification) (Ali and Morgan 1990).

Primer pheromones have particularly evolved in social insects, where they represent the primary driving force in the evolution of social coordination and the maintenance of colony homeostasis (Le Conte and Hefetz, 2008). Among honey bee pheromones, the queen signal and brood pheromones (discussed in detail below) are essentially primer pheromones (also possessing some releaser functions), while most worker pheromones should be considered releaser pheromones.

In the following paragraphs, the main honey bee pheromones are explained based on the bee caste to which they belong and the glands responsible for their production. In the first section, the effect (or effects) exerted by each pheromone on recipients and the honey bee colony will be demonstrated, while the neural physiological and molecular mechanisms of response to these chemicals will be discussed in the second section.

Queen Pheromones

The honey bee queen is the primary regulator of colony function. This regulation is largely achieved through the use of pheromones produced by various glands and released as a complex chemical mixture known as the "queen signal."

What is the Queen Signal?

The queen signal primarily functions as a primer pheromone, inducing numerous physiological and behavioral changes in worker bees that lead to colony homeostasis through the establishment of social hierarchy and maintenance of the queen's reproductive dominance.

Specifically, the effects of the queen signal include maintaining worker cohesion, suppressing queen rearing, inhibiting worker reproduction, and stimulating worker activities: cleaning, building, guarding, foraging for nectar and pollen, and feeding brood. It is known that when the queen becomes old or sick (low pheromone signal) or dies (no pheromone signal), workers are directed to rear new queens from young brood within 12 to 24 hours.

Removal of the queen in the absence of young brood soon leads to colony decline: workers cease their activities and begin laying unfertilized eggs that develop into adult drones. The colony becomes disorganized, unfit, dirty, susceptible to diseases, and vulnerable to predators; the population rapidly declines toward certain death.

In addition to its primer effects, the queen signal also exerts a releaser attractive effect: it calls workers to surround the queen in an attendant group and stimulates them to feed and groom her.

In young queens before mating flights, it functions as an attraction for drones during mating flights. Additionally, during swarming, it holds the swarm together.

Main Components of the Queen Signal

Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP)

Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP) is by far the most studied and recognized chemical signal in honey bee society. Its initial identification dates back to 1960, when 9-oxo-2-decenoic acid (E), known as 9-ODA, was identified as a substance secreted by the queen's mandibular glands (Barbier and Lederer 1960; Callow and Johnston 1960). The secretory organs are a pair of sac-like glands located inside the head above the base of the mandibles. The glands open through a short duct at the base of the mandible, and their secretion passes along a deeper canal surrounded by hairs (Bille 1994).

Important Discovery

In 1988, Slessor and colleagues discovered four additional compounds secreted by the mandibular glands that act synergistically with 9-ODA.

- Two enantiomers of 9-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (9-HDA)

- Methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (HOB)

- And 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenylethanol (homovanillyl alcohol [HVA])

These five components together, compared to any single substance alone or in combination, were more active in forming groups of active worker bees. It was concluded that these five chemicals together form the basis of QMP secretion, representing the primary constituent of the queen signal.

Several authors have analyzed the evolution of QMP components during queen aging, from emergence to full dominance. Generally, the amount of volatile materials was found to increase with age, but findings regarding different compounds and their relative quantities were contradictory among authors, as shown in the studies described in this post.

Evolution of QMP Components During Queen Aging

Engels et al. (1997) identified three different ontogenetic patterns of QMP in queens:

Pattern 1: Early Virgin Queens

Presented weak signals, with oleic acid (OLA) as the main component

Pattern 2: Mating Queens

Intensified the signal, which mainly included 9-ODA along with OLA and small amounts of 9-HDA

Pattern 3: Dominant Post-Mating Queens

Showed strong signals with high concentrations of 9-ODA along with medium ratios of 9-HDA, less OLA, and small amounts of oxygenated aromatic compounds

The researchers suggested that these oxygenated aromatic compounds, particularly the late-emerging HOB and HVA, could represent the typical signal of old, egg-laying, and dominant queens.

Three ontogenetic patterns have been identified for queen mandibular pheromones: 1) With oleic acid 2) Mainly including 9-ODA along with 9-HDA and small amounts of OLA 3) High concentrations of 9-ODA along with medium amounts of 9-HDA and small amounts of OLA.

Engels et al. (1997) identified three different ontogenetic patterns of QMP in queens, indicating the evolution of chemical signals with increasing age and mating experience of the queen. These patterns include early virgin queens, mating queens, and dominant post-mating queens.

Comparative Studies of QMP

Plettner et al. (1997) compared the amounts of QMP components between 6-day-old virgins and 1-year-old mated laying queens from several species. They found that mated Apis mellifera queens had significantly higher levels of 9-ODA, 9-HDA, HOB, and HVA, while the opposite trend was observed for 10-HDA and 10-HDAA, which are typical components of worker mandibular glands and are produced in higher amounts by virgin queens.

Slessor et al. (1990), comparing virgin queens with mated queens of different ages, found slightly different results, with nearly constant levels of 9-ODA across different groups, higher levels of 9-HDA in virgin pairs compared to mated queens, and levels of HOB and HVA in the oldest mated queens compared to virgins and young mated queens. In all cases, pheromone levels were higher in adult, mated, and laying queens.

Conversely, Rhodes et al. (2007), comparing 7-day-old virgin and mated queens, found that the former had higher levels of 9-HDA, 9-ODA, and 10-HDA than the latter. In a similar comparison, Richards et al. (2007) found that the amounts of 9-ODA, 9-HDA, and HVA were all significantly lower in mated queens compared to virgins, although extracts of mandibular glands from mated queens were more attractive to workers than those from virgin queens.

Scientifically Proven Fact

Typically, pheromone levels are higher in old and mated queens compared to virgin queens. Extracts from mandibular glands of mated queens are more attractive to workers than those from virgin queens.

Finally, Strauss et al. (2008), analyzing mandibular gland compounds from three groups of virgin queens, drone-laying queens, and mated laying queens, found similar amounts of 9-ODA in the three groups and increasing amounts of all other components (9-HDA, 10-HDA, 10-HDAA, and HVA) except HOB, from virgin to mated queens. The constant level of 9-ODA, corresponding to a higher relative proportion in virgin queens, indicates that 9-ODA plays a greater role in attracting drones to virgin queens than in attracting attendants in mated queens. In contrast, 9-HDA, 10-HDA, 10-HDAA, and HVA show positive correlation with the queen's reproductive potential and ovary activation (Strauss et al. 2008).

These contradictory results indicate that the role of individual QMP components in the queen signal is not fully understood, and there may be additional unknown compounds in the mandibular glands of mated queens that synergize with 9-ODA and 9-HDA in attractive function.

Numerous compounds exist in queen mandibular gland extracts, some remaining unknown and possessing multiple and sometimes contradictory properties in worker attraction.

Worker Attraction: The Retinue

The first discovered functions of QMP were due to its attractive properties toward workers: queen retinue formation and swarm cluster formation and maintenance (Kaminski et al., 1990; Winston et al., 1989).

When the queen is stationary on the comb, she is surrounded by a circle of workers called the "retinue" or "attendants" who face her, feed her, touch her, and lick her. Typically, this group consists of eight to ten workers. Several studies showed that QMP and its components are responsible for retinue formation (Free 1987), and this is supported by the fact that worker attraction to the queen can be related to changes in QMP pattern.

When a virgin queen mates and begins laying eggs, the attention of attendant workers increases, and of course decreases with aging. The degree of queen attractiveness is zero at 0-1 days old, moderate from 2 to 4 days old, and high from 5 days to 18 months old (De Hazan et al., 1989). Richards et al. (2007) tested extracts of mandibular glands from virgin and inseminated queens on worker retinue responses and found that extracts from inseminated queens were more attractive than those from virgin queens, and extracts from queens inseminated with more than one drone were more attractive than those from queens inseminated with a single drone. This indicates that mating is an important factor for the development of the queen's chemical signal and its attractive effect on workers.

Interesting Discovery

Extracts from mandibular glands of mated queens are more attractive to workers than those from virgin queens, and even more interestingly, the above extract is more attractive for queens that have mated with more than one drone than for queens that have mated with a single drone!

In 2003, Keeling et al. identified four additional compounds produced by the queen that act synergistically with QMP in attracting workers to form retinue groups: coniferyl alcohol (CA), methyl oleate (MO), hexadecan-1-ol (PA), and linoleic acid (LA). The first is secreted by mandibular glands, while the rest are produced in different parts of the queen's body. These substances alone were inactive, but when combined with QMP, they were found to greatly increase queen retinue activity.

Additionally, in a recent study, Maisonnasse et al. (2010a) showed that queens artificially deprived of mandibular glands can still attract workers, indicating that QMP is not the only pheromone that can attract workers and that in its absence, other substances can play its role.

Worker Attraction: Swarming

Swarming is the way in which the colony reproduces itself. Workers rear new queens, and the first queen to emerge kills the others and becomes the new colony after mating, while the old queen leads the swarm toward a new nest. The presence of the queen is essential for keeping the honey bee swarm together: if the queen dies or cannot fly, the swarm soon returns to the parent hive. Queen attractiveness to the swarm is established using pheromonal signals, mainly QMP. In 1989, Winston et al. compared the effects of the queen, mandibular gland extracts, and the five-component mixture on bee swarms and showed that the component mixture and gland extracts showed similar effects, while the queen alone always had the strongest attraction. This showed, like retinue behavior induction, that other additional mandibular components may be involved in swarm formation.

Swarming is a way for colony reproduction that is influenced by the old queen's pheromones. This is typically created by reducing queen attractiveness using pheromonal signals, mainly QMP.

Drone Attraction: QMP as a Sex Pheromone

Immediately after its discovery, it became clear that QMP is used by virgin queens to attract drones during mating flights (Gary 1962). Specifically, using 9-ODA from an artificial queen clearly showed that it attracts drones (Gary and Marston 1971).

In further experiments, various combinations of 9-HDA, 10-HDA, and HOB were also found to increase the number of drones making contact with artificial queens. 9-HDA and 10-HDA were specifically responsible for increasing mating contacts, although they were only active at short range, unlike 9-ODA, which also acted at greater distance (Brockmann et al. 2006; Loper et al. 1996). By comparing QMP components in virgin and mated queens, it appears that 10-HDA is more prominent in the former while it decreases significantly in quantity in the latter (Plettner et al., 1997). The fact that 10-HDA is produced in large quantities by virgin queens indicates its role as a sex pheromone in mating behavior.

When tergal gland extracts were added to 9-ODA, an increase in mating behavior frequency was observed (Renner and Vierling 1977). This indicates that multiple glandular sources can cooperate in enhancing the effectiveness of the pheromonal stimulus, leading to a stronger response and more complete performance of the mating behavior sequence. Therefore, the relative contribution of different QMP components and other glands to the sex pheromone blend is still not entirely clear.

Note on Sex Pheromones

QMP functions as a sex pheromone. 9-HDA and 10-HDA are specifically responsible for increasing mating contacts, although they are only active at short range, unlike 9-ODA, which also acts at greater distances.

Unique Queen: Suppression of Queen Rearing and Swarming

Many insect societies are monogynous, meaning there is one queen per colony. In small and primitive social species, queen dominance is maintained through physical fighting and competition among females. In contrast, in large monogynous colonies, physical dominance is not feasible, and a more efficient system based on pheromonal signals has evolved to maintain queen dominance.

As previously mentioned, removal of the queen from an A. mellifera colony leads to construction of special cells (queen cups) by worker bees to rear new queens (Winston 1992), but the precise mechanism by which this occurs remains somewhat unclear.

Rearing new queens in a colony has two main domains: colony reproduction through swarming and queen replacement when she becomes old or weak (this phenomenon is known as supersedure) or if she dies due to beekeeping practices or pathology.

QMP, through its dispersion in the colony, suppresses both queen replacement and swarming (Winston et al. 1989). Several studies have been conducted to clarify the mechanisms of QMP dispersion within the colony and its transmission among workers. In 1991, Naumann et al. identified a group of retinue workers as the first actors in transmitting queen pheromones to other workers and self-organization as a means of transmitting pheromones from mouthparts and head to the worker's abdomen. QMP distribution appears to be influenced by colony size, as in populous colonies, peripheral workers obtain less pheromone than in less populous nests (Naumann et al., 1991). This explains why populous colonies swarm: the "queen present" pheromone signal decreases as the colony grows because pheromone dispersion decreases, and thus workers perceive less pheromone, resulting in colony reproduction through queen rearing and colony swarming. When the queen dies or is removed, the pheromone signal completely disappears, and workers are stimulated to rear new queens.

The role of QMP in suppressing queen rearing initiation was confirmed by several studies; showing that administration of synthetic QMP to orphaned colonies (i.e., queenless colonies) suppresses queen cup production (Pettis et al., 1995) if administered within 24 hours after queen loss; in fact, if synthetic QMP is applied 4 days after queen loss, no effect is observed, indicating that QMP inhibits queen rearing initiation but not maintenance of already built cells (Melathopoulos et al., 1996).

QMP Function in Suppression

QMP inhibits queen rearing initiation but not maintenance of already built cells. Consequently, new queens emerge in newly built queen cells.

Other Queen Pheromones (Beyond QMP)

Mandibular glands are not the only source of chemicals that play roles in social cohesion and colony homeostasis. For many years, researchers thought that QMP alone could explain the regulation of all colony functions. Later, other pheromone sources were discovered that matched the multicomponent nature of the queen signal. As early as 1970, Velthuis noticed that queens whose mandibular glands had been removed could still exert some regulatory functions on workers (retinue behavior, inhibition of queen cup construction, suppression of worker ovary development). But it was not until 2010 that Maisonnasse et al. confirmed these results and showed that mandibular gland-deprived queens maintain their full regulatory role in the functions mentioned above. The aforementioned authors discovered that levels of QMP components in deprived and control queens were similar, except for 9-ODA, which was not identified in the former. This indicates that only 9-ODA is uniquely produced and stored in mandibular glands, while other substances (HOB and 9-HDA) appear to have another production source in the queen's body. 9-ODA has always been considered the main substance acting on retinue behavior, but this is maintained in deprived queens, indicating that other queen substances have the potential to replace 9-ODA in eliciting this behavior.

New Discovery

Only 9-ODA is uniquely produced and stored in mandibular glands, while other substances (HOB and 9-HDA) appear to have another production source in the queen's body.

Alternative sources of queen signal have been identified in tergal, tarsal, Dufour's, and Koschewnikov glands. Their secretions can cooperate with QMP in the queen signal composition or be responsible for one or more specific regulatory functions.

Latest comments